Monitoring Efforts

It is hypothesized that blooms on the Georgia coast will increase due to nutrient runoff caused by increased shoreline development and global rises in temperature. To fill the gap and begin a monitoring program for HABs in Georgia, SECOORA is supporting Natalie Cohen and her team at the University of Georgia Skidaway Institute of Oceanography and Marine Extension & Georgia Sea Grant to document the relationship between cell densities of HAB species and water quality parameters in the Skidaway River Estuary. The project goal is to identify environmental conditions that are conducive to HAB formation in Georgia estuaries. By understanding these conditions, the team and stakeholders can better predict and mitigate the impact of these blooms on our coastal ecosystems.

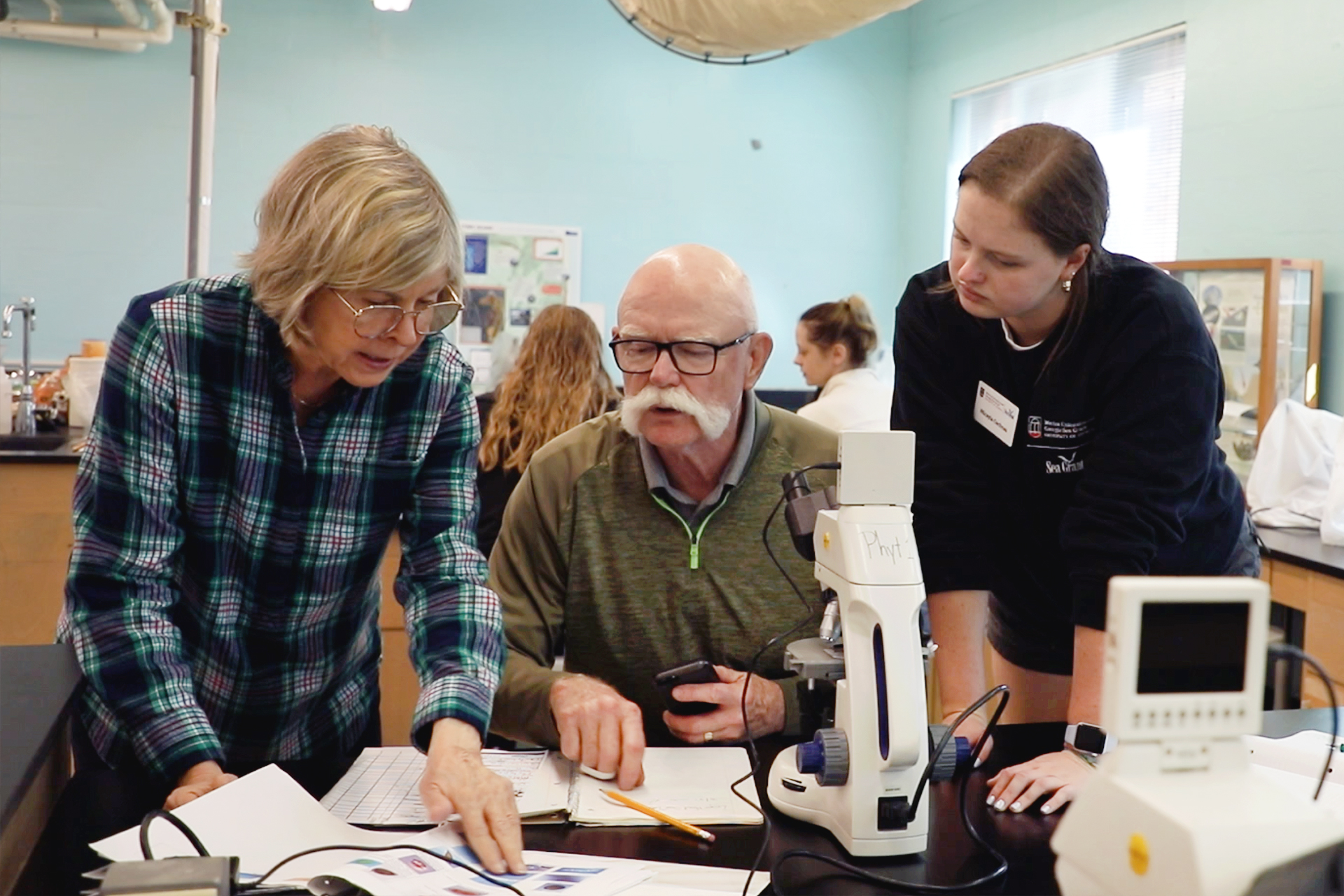

Empowering the Community

This monitoring program is the first step in establishing a regional notification network in which HAB occurrences are communicated to local residents and regional aquaculture organizations. By releasing daily Akashiwo cell densities, coastal GA stakeholders can evaluate whether to use estuary water for aquaculture purposes, or delay until estuary conditions improve.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is Akashiwo sanguinea?

Akashiwo sanguinea (A. sanguinea) is a harmful algal blooming organism. Akashiwo is a single-celled eukaryote that is capable of both photosynthesizing and consuming prey. It is not clear whether it produces a toxin, but it is known to produce a soap-like substance that negatively impacts wildlife by clogging fish gills and coating bird feathers. When bird feathers are coated in this substance, they lose their water-repellant properties and insulation abilities.

Why is Akashiwo sanguinea a concern?

High cell densities (~250 cells/mL) of A. sanguinea were the suspected cause of an oyster larvae die-off event in the Skidaway River Estuary (Pfeiler 2020). The exact cause of the event is unclear, and could be related to nutrient availability, temperature, salinity, and/or picoplankton prey presence selecting for the growth of A. sanguinea (Pfeiler 2020).

How is Akashiwo sanguinea being measured?

The University of Georgia Skidaway Institute of Oceanography employs a comprehensive monitoring approach for HABs in the Skidaway River Estuary. The team conducts weekly measurements of water quality, nutrients, and cell densities in non-summer months. During summer months and through fall, the sampling frequency increases daily to capture seasonal biological and chemical transitions in the phytoplankton community, and allow them to begin documenting their relationship with water quality parameters. Cell counts are obtained via aFlowCAM fluid imaging system.

How can I learn more?

Interested in learning more about Harmful Algal Bloom research in Georgia? Here are some helpful links:

- Dr. Natalie Cohen’s Lab Website

- MS thesis of Liz Pfeiler – first documentation of Akashiwo in the Skidaway River Estuary

- Dr. Natalie Cohen’s Evening at Skidway presentation, “Harmful Algal Blooms in Coastal Georgia”